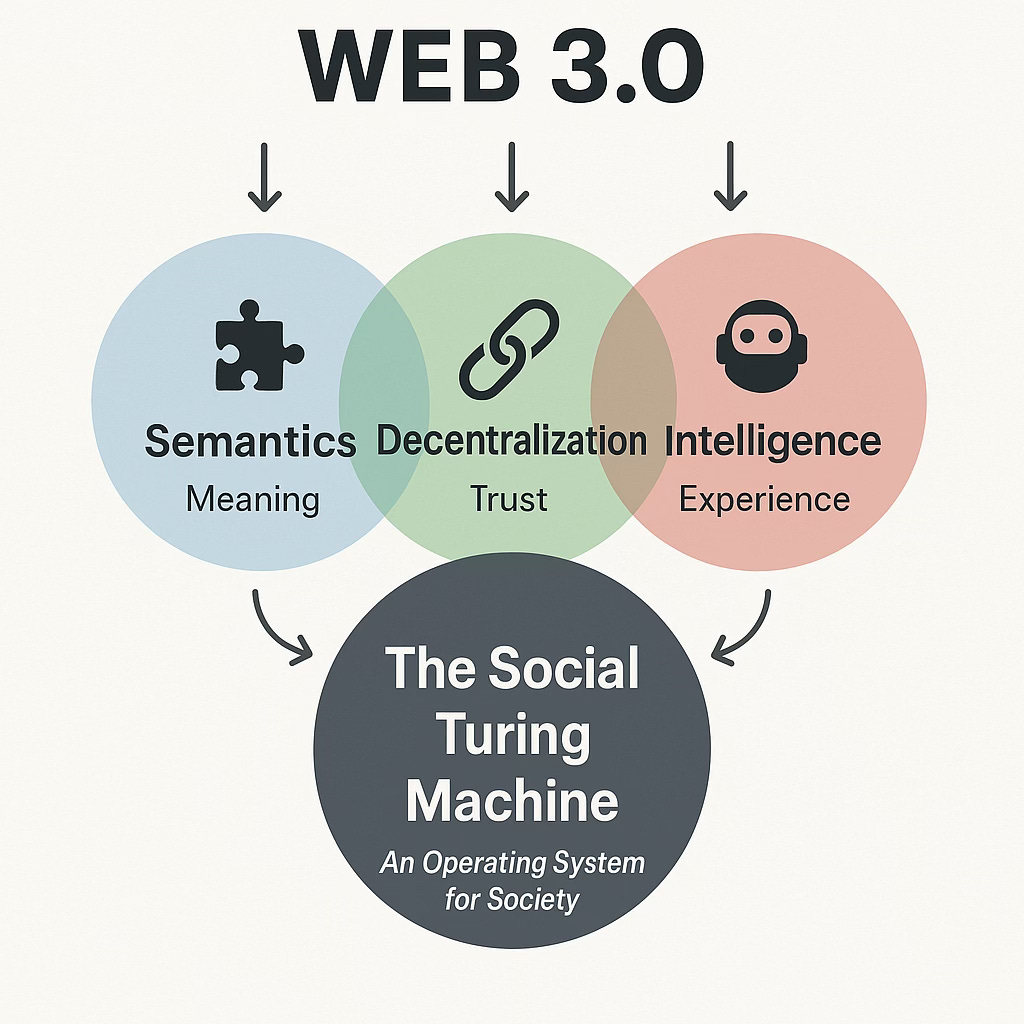

The Real Web3.0: When Meaning, Trust, and Intelligence Finally Converge

From the Semantic Web to Decentralization to AI — tracing three decades of evolution toward the Social Turing Machine, a new operating system for society.

When you hear Web3, what comes to mind?

Crypto? Blockchains?

The post-2008 wave of techno-rebellion that promised to fix everything the old web broke — money, trust, even truth itself?

For most people, Web3 now feels inseparable from speculation and digital assets, another chapter in the long saga of boom and bust. But long before tokens and NFTs, Web 3.0 had a very different meaning.

It wasn’t about trading. It was about structure — about how information, value, and meaning could finally merge into one networked logic.

So before we chase the latest buzzwords, it’s worth slowing down and asking:

What was Web3 originally supposed to be?

And if we truly believe in a “third generation” of the internet —

then what exactly were the first two?

Because sometimes, the only way to glimpse the next paradigm

is to rewind the story and look at where the previous ones stopped.

The Two Paradigm Shifts We Already Lived Through

If you’ve been online long enough, you’ve already lived through two revolutions —

and maybe didn’t even notice when the second one ended.

Web1.0 (1990s–2005): The Read-Only Web

It began quietly.

Dial-up tones. Static pages. A world of hyperlinks and portals — Yahoo, AOL, Sina, Sohu — a digital frontier built from text and patience.

Web1.0 was a library, not a conversation.

You came to read, not to respond.

Information flowed in one direction, from the few who could publish to the many who could only consume.

But there was a kind of magic in that limitation.

You could get lost in the raw curiosity of discovery — stumbling upon personal homepages, hand-coded HTML shrines to hobbies and ideas. The web felt open, infinite, and strangely personal.

It gave us freedom to read, to explore, to learn without permission.

Yet we were still outsiders, peering through the glass.

Web2.0 (2005–2020s): The Interactive Web

Then came the next revolution.

Suddenly, the web started to talk back.

Web2.0 transformed static pages into living ecosystems.

Blogs. Wikipedia. YouTube. Facebook. Weibo. TikTok.

A billion keyboards lit up. Creation was no longer reserved for coders or media moguls — anyone could upload, comment, remix, participate.

It felt like a collective awakening:

for the first time, everyone had a voice.

But the revolution came with a hidden clause.

The platforms that empowered our expression quietly captured its value.

We built the content; they built the walls.

We filled the feeds; they sold the attention.

Our photos, our clicks, our friendships — all became inputs for algorithmic empires.

Web2 democratized creativity but privatized the infrastructure of connection.

Web1 gave us the freedom to read.

Web2 gave us the freedom to speak.

Web3 must give us the freedom to own.

Because what good is a voice if someone else owns the microphone?

What good is a platform if you can’t leave with your data, your identity, your work?

Many of us who came of age in the Web2 era can feel it — the ceiling pressing down.

The sense of endless possibility that once defined the web has ossified into closed systems and content factories. The open frontier became a walled garden.

We are the generation that watched the internet grow up —

and now, we are watching it grow old.

So where does the next revolution begin?

II. The Three Source Streams of Web3

The story of Web3 didn’t begin with Bitcoin or NFTs.

Its roots stretch much deeper — across three parallel genealogies: technical, philosophical, and economic.

Each tried to answer the same question from a different angle:

How can we make the web more human, and at the same time, more intelligent and more trustworthy?

Together they form the three great rivers that eventually converge into today’s idea of Web3.

1. The Semantic Web — Tim Berners-Lee’s Lost Dream (2001)

At the dawn of the 21st century, the web’s inventor himself tried to evolve it.

In 2001, Tim Berners-Lee published his manifesto for the Semantic Web in Scientific American.

His ambition sounded almost mystical:

“The Web should not only be readable by humans — it should be understood by machines.”

In Berners-Lee’s imagination, the internet would transform from a chaotic library of documents into a web of meaning — a distributed knowledge system where machines could interpret, reason, and act.

Every piece of data would carry context — relationships, intent, hierarchy — encoded in languages like RDF, OWL, and SPARQL.

Machines would no longer just display information; they would understand it.

It was the dream of a “knowledge web”: one where AI assistants could book flights, file taxes, or answer complex medical questions by reasoning through structured data.

But the dream hit a wall.

Building semantic ontologies required experts fluent in logic and metadata.

Standardization (led by W3C) moved slower than industry innovation.

No killer app or business model emerged to justify the cost.

The Semantic Web became a paradox — a framework too elegant to die, too complex to live.

Its legacy survived quietly in knowledge graphs and search algorithms, but its public promise faded.

Still, Berners-Lee planted a seed:

that meaning, structure, and reasoning must one day return to the web.

2. The Decentralized Web — Gavin Wood’s Breakaway (2014)

Fast-forward thirteen years.

The world had changed — economically, politically, psychologically.

The 2008 financial crisis shattered trust in institutions.

People began to realize that the “open” Web2 was in fact owned by a handful of platforms and payment processors.

Into that disillusionment stepped a new narrative: decentralization.

In 2014, Gavin Wood, co-founder of Ethereum, published his Web3 Manifesto.

His definition of the next web wasn’t about meaning — it was about sovereignty.

He proposed an internet that no longer depended on governments or corporations for validation.

Instead, trust would be embedded in cryptographic protocols and smart contracts — software that executes itself when conditions are met.

Code is law.

Trust math, not men.

The Decentralized Web inverted the Web2 hierarchy:

No intermediaries controlling identity or data.

No single gatekeeper regulating access.

No opaque algorithms deciding what you see or earn.

If the Semantic Web sought truth through understanding,

the Decentralized Web sought legitimacy through verification.

And it had something the Semantic Web never did —

a running prototype: Bitcoin.

A system that worked, scaled, and held monetary value.

Ethereum expanded it further with smart contracts, turning “money as code” into “society as code.”

Communities formed. Capital followed. Ideology ignited.

But as the movement grew, it drifted from its philosophical core.

The decentralized ideal was absorbed by speculation — ICOs, DeFi, NFT mania.

“Web3” became shorthand for crypto, stripped of the intellectual depth it once hinted at.

Two rivers diverged:

The semantic current retreated into academia.

The decentralized current flooded into markets.

And the web, again, found itself split between meaning and money.

3. The Intelligent Web — The Age of Machine Understanding (2006–)

While scholars debated logic and cypherpunks coded blockchains, Silicon Valley built a third universe — one of data and prediction.

This was the rise of the Intelligent Web, driven not by ideology but by optimization.

Between 2006 and 2016, the web turned into a data refinery.

Google’s Knowledge Graph, Facebook’s Social Graph, Netflix’s recommendation engine, Amazon’s personalization algorithms — all were pieces of a vast feedback machine learning how humans think, buy, and behave.

It worked. Almost too well.

The internet became intimate — eerily so.

We no longer searched for information; information found us.

But the intelligence came at a cost:

centralized control, opaque algorithms, and an extractive data economy.

Our clicks became fuel. Our attention became the product.

If the Semantic Web was a cathedral of logic,

and the Decentralized Web was a protest camp for autonomy,

the Intelligent Web was a corporate refinery — efficient, profitable, but hollow.

Three Streams, One Destination

Each stream pursued a different truth:

The Semantic Web imagined an internet where machines could truly understand meaning — a grand attempt to give logic and structure to information itself. Its strength was in knowledge precision, but it proved too complex and slow to scale.

The Decentralized Web, championed by the blockchain movement, aimed to build systems that could run without centralized trust. Its power lay in transparency and legitimacy, yet it often lacked the nuance and semantic depth needed to make those systems interpretable by humans or AI.

Meanwhile, the Intelligent Web, driven by AI and big data, focused on personalization and adaptive experience. It mastered prediction and convenience, but sacrificed openness and ethical clarity, turning intelligence into yet another centralized commodity.

All three were incomplete.

Each solved one layer of the human–machine relationship but neglected the others.

Now, as Large Language Models (LLMs) bring semantics to life,

as cryptographic protocols mature beyond speculation,

and as the public demands transparent, explainable intelligence —

these three rivers are beginning to merge again.

When they finally converge, we will no longer talk about the web as a set of platforms,

but as a living structure of meaning, trust, and intelligence —

what I call the Social Turing Machine.